New Port Authority Fare Changes Do Not Remove Fare Cost Burden on Low Income and Minority Riders, and Highlight Need for a Low-Income Fare Program

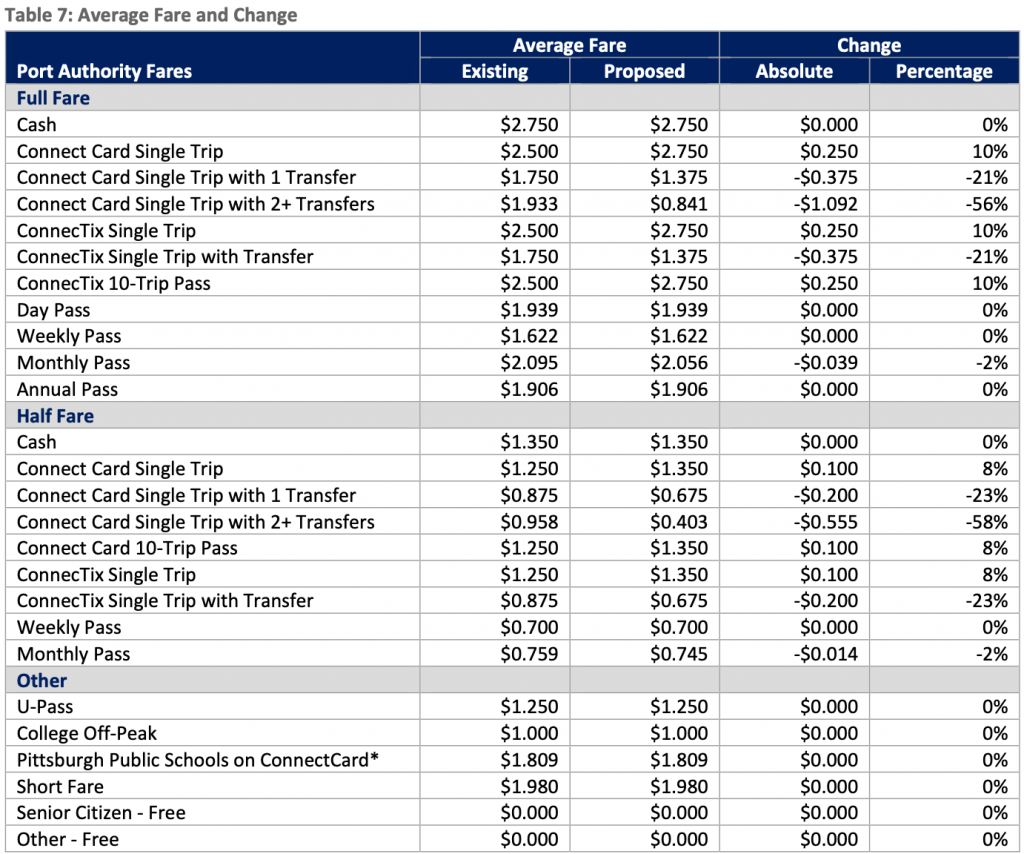

Effective January 1st, 2022, the Port Authority will be implementing a rolling pass program that “starts” a weekly or monthly bus pass on the first day of its usage, rather than bus passes that follow a calendar schedule. The Port Authority will also be implementing changes for stored value CONNECT card users: a 25 cent increase in per-trip cost coupled with free transfers within a three-hour window.

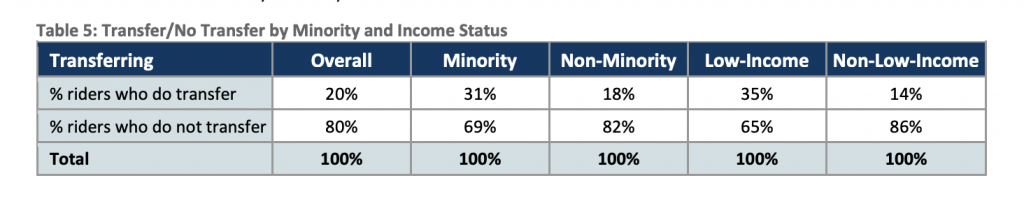

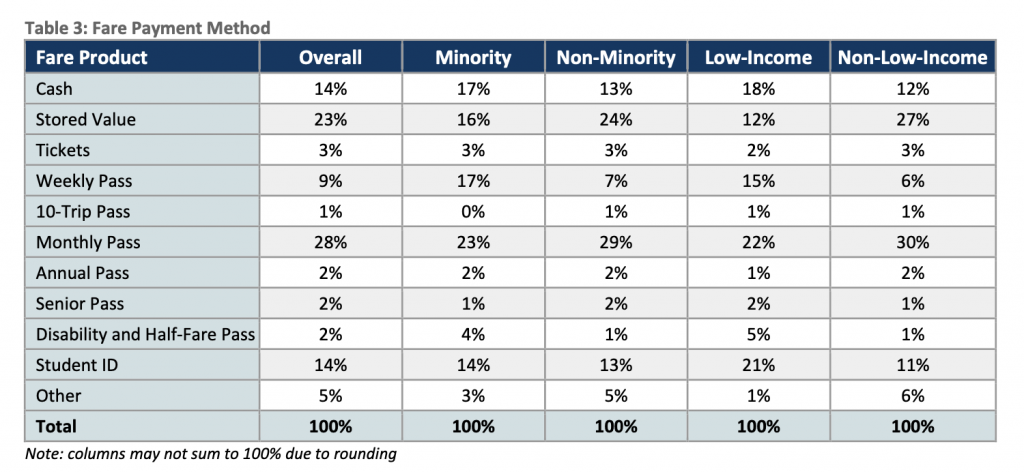

While the bus pass changes will likely make bus pass purchases more useful and accessible to some, the stored value CONNECT card changes will not alleviate fare cost burdens on the majority of transit riders, including for low-income riders and riders of color. (Low-income riders in the Port Authority’s Title VI Fare Analysis are identified as those living in households with an annual income of <$25,000. Minority riders are all those who did not exclusively identify themselves as white/Caucasian in Port Authority’s 2014 rider survey.) In fact, the Port Authority’s Title VI data shows that by a nearly 2:1 ratio, low-income riders and minority riders using the stored value CONNECT cards will see an increase in transit fare costs and will not benefit from free transfers, because they only take single trips within a three hour window. This highlights why it is more urgent than ever that Port Authority implement a low-income fare program such as that called for in the Fair Fares for Full Recovery Campaign.

By a nearly 2:1 ratio, low-income riders and minority riders using the stored value CONNECT cards will see an increase in transit fare costs

Moreover, because these coming fare policies do not propose any changes for riders paying with cash, Port Authority continues to maintain a fare structure in which poor riders pay more money for worse transit service. In fact, more trips made by low income and minority riders are paid for with cash than are paid for with stored value CONNECT Cards. Cash-paying riders currently pay the highest fare for service, at $2.75 for every trip and another $2.75 for each transfer. Routes with high cash usage run through disproportionately low-income and high minority communities, and these routes often require more transfers with more limited and infrequent service to access critical amenities. Moreover, there is low CONNECT card adoption in these communities by design, because access points for charging or purchasing CONNECT Cards like ticket vending machines and Giant Eagle/Goodwill stores are less available. It is therefore imperative that, at a minimum, the Port Authority allow low-income riders paying cash to receive the same free transfer benefit offered to CONNECT card users, by reinstating the Port Authority’s paper transfer tickets as PPT and allies have called for in its #FairFares Platform.

Port Authority continues to maintain a fare structure in which poor riders pay more money for worse transit service.

While PPT supports fare programs that make using the transit system more efficient, it is critical that low-income riders see some relief from the disproportionate burden that transit fares represent. A critical social utility that relies on user fees for revenue is by nature regressive; Port Authority could also begin to shift costs for providing the service to corporations by implementing a bulk discount pass program for corporations, human service organizations and developers to buy into. As an interim solution, the Port Authority should follow through on its goal to create a low-income fare program, as it was named a top priority in their long-range planning effort. Given that these Jan 1’st fare policy changes do not remedy transit fare cost impacts for many and will likely exacerbate costs for some of our region’s most marginalized riders, advocates are calling on the Port Authority to take decisive steps to make fare equity a reality, now.